The Saturday after arriving back from San Francisco, my friend Isaac and I arranged to climb the Sandia mountains from the base to the summit. I had previously been up to the ridgeline on the cable car, but did not make it all the way to the top, and walking it seemed like a much more adventurous plan. Isaac invited another friend of his, making it a party of three. We took the La Luz Trail, a 7.8 mile route that winds its way up from the foothills to the cable car. Some parts of this route were very steep and one section involved clambering over boulders to progress up the mountain. The trip up provided an ever-changing view, beginning with scrubby desert terrain punctuated only by small plants and cacti, before we entered into pine forest and then emerged into an autumnal landscape of red-, orange- and yellow-leaved deciduous trees.

|

| Flying the flag for New Mexico with an Albuquerque backdrop |

|

| Still a long way to go, surrounded by cliffs and woodland |

|

| Positioned precariously, close to a sheer drop near the summit |

When we reached the cable car station, the information boards provided details of the mountains' geological history and fantastic views from the crest to the extinct Albuquerque volcanoes beyond the Rio Grande, and ultimately as far as Mount Taylor, 66 miles away. From the cable car, another 1.8 miles was enough to reach Sandia Crest, the summit itself, at 3,255 metres above sea level, around one mile of elevation higher than Albuquerque. The summit was very windswept but the feeling of relief at having reached the top meant the chilly air didn't matter. The route back down felt like it was much shorter than the way up, and we reached the bottom at sunset, having completed a total of 16.8 miles.

|

| TV and radio antennae for the city, at the summit |

|

| The ant city of Albuquerque |

|

| Almost dark by the time we finished! |

The following day I travelled a bit further afield, north towards Santa Fe. This was to visit another natural site, Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument. In some respects, this landscape was reminiscent of Arches National Park in Utah, owing to the fact that it was mostly hidden until we actually climbed up into the rocks. This park consisted of a large number of bizarre-looking 'hoodoo' rock formations resembling, as the park's name suggests, large tent-like structures. There was one short path leading up through a narrow gorge and then over rocky ground to a cliff top above the gorge, which made for an uneasy walk. The sights of the park were truly incredible though, and utterly alien.

|

| Tent Rocks from the bottom of the trail |

|

| Looking up through a beautifully eroded column |

|

| Pointed hoodoos |

|

| A collection of hoodoos |

|

Hoodoos in the centre of the park,

with future ones being formed on the left |

I returned in the same direction the next Saturday, travelling with three classmates through Santa Fe to a lonely rural region beyond the small town of Española. This land fell under the San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant, land which was granted to the descendants of the Hispanic residents who had historically controlled this land. The USA's westward expansion led to the seizure of large swathes of land particularly in the modern Western states, and these lands were only gradually returned to indigenous tribes and descendants of Spanish immigrants from the early twentieth century onwards.

|

| San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant |

My classmates and my professor, who specialises in New Mexican history, were on the land grant to assist the land grant heirs and residents in the construction of a new trail suitable for an all-terrain vehicle to drive up a short slope to access a cemetery. In this small cemetery were buried the relatives of many of the land grant residents, and the trail's main purpose was to allow the most elderly people to visit the cemetery. This seemingly low-key occasion actually constituted part of a much greater process as it represented one small piece of collaboration between the land grant residents and the US Forest Service, a body of the federal government and therefore a part of the same organisation that had stripped these people of their lands in the first place. One issue that was sorted out was the redrawing of the boundary of the adjacent wilderness area so as to omit the cemetery from the wilderness and ensure the land grant retained the control of the cemetery land. Despite this dark aspect of the history between the land grant people and the government, there was a sense of harmony on the day between the Forest Service staff and the land grant people. So momentous was the event that the congressman of New Mexico's 3rd congressional district (covering 15 of the state's 33 counties) was on site; his and others' speeches reinforced the extent to which the day symbolised a shift in relations between the Forest Service and the land grant. The event was even covered on the University of New Mexico's website, and the article may be read here:

http://news.unm.edu/news/unm-assists-land-grant-forest-service-on-heritage-lands

|

| My classmates and me with congressman Ben Ray Luján |

Once the formalities were over, the actual labour began. This was a far cry from the kind of road that would be built in the UK, because the purpose of all the volunteers was really only to form a smooth, vegetation-free route up the short slope to the cemetery, as well as to dig out drainage channels so that rainwater could be diverted from the trail to prevent erosion. This was done using tools I knew, like the shovel and the adze, and tools I'd never heard of, like the McLeod and the pulaski. In the end, it didn't take very long to complete the work and we left having met some interesting characters from the land grant and with a sense of satisfaction at leaving the land grant people so grateful for their new infrastructure.

|

| Manual labour on the land grant |

The inhabitants of the land grant were definitely an intriguing bunch. Like the Pueblo people I had encountered at Taos, these people lived in a rural area using basic methods to survive using a subsistence lifestyle, farming the land in a manner very similar to their ancestors. Unlike the Puebloans, though, these individuals had a much more European feel to them due to the fact that they are descendants of Spaniards who came to North America in the decades following Columbus' arrival and Cortes' conquest of Central America. Their outdoor nature was emphasised by the fact that two of the people present were over 90 years old whilst a third was under the age of 10, showing the importance of the cemetery and of community to all individuals of all ages. Secondly, the cemetery's role in their society was shown when we took part in a rosary before beginning the work. This involved kneeling down for about forty minutes whilst the Hail Mary prayer was repeated in Spanish, and other prayers were also spoken. Some of these were sung, and I was told the traditional style of singing originated in Spain but has since died out there and is now unique to the north of New Mexico. The Spanish prayers, the ramshackle cemetery with its crooked wooden crosses, the community of old and young, Anglo and Hispanic kneeling together, all in a dry and inhospitable land under a warm October sun, combined to make this ceremony just as moving a religious service as any I can think of.

|

| Cemetery cross |

|

| The Rio de Chama |

Once we left the land grant, our professor took us for a brief tour around some interesting features of the nearby area, including a couple of locations from the book about New Mexican history we had been reading in our class. One of these was the enormous Echo Amphitheatre cavern, a vast hollow eroded into a cliff, and which also produced a wonderful reverberation of sound. After that, we had time to see the dam at Abiquiu, and our professor then treated us all to a meal of traditional northern New Mexican food at a restaurant in Española; I had a delicious burrito of lamb with red chilli beans, lamb having been a staple meat ever since the European arrival in this region of the modern USA.

|

| Echo Amphitheatre |

|

| An unnerving overhang |

|

| Abiquiu Reservoir |

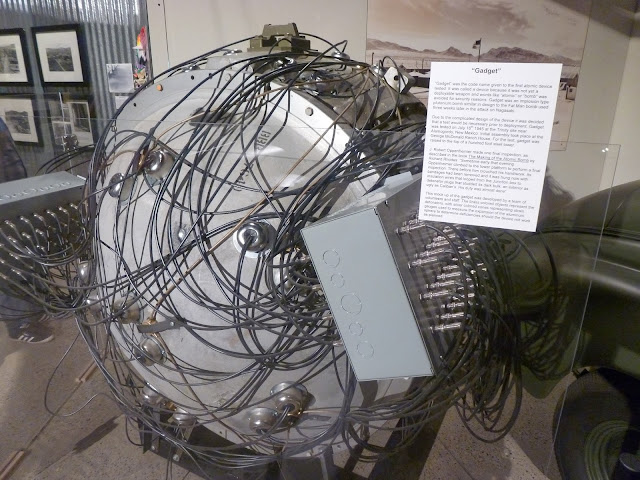

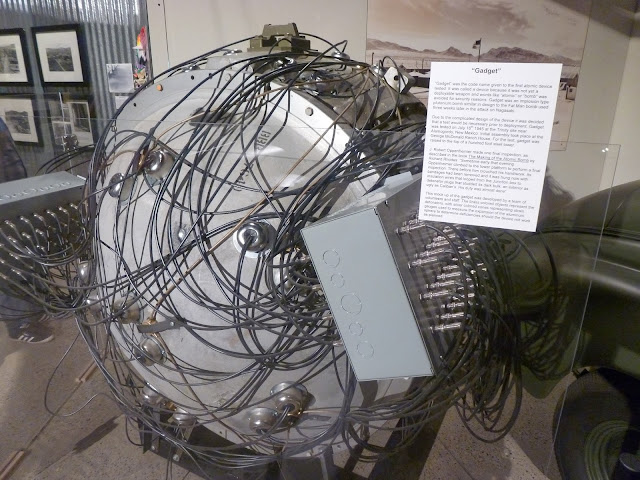

After a long day on the Saturday, I was eager to relax a little more on the Sunday, but still found time to take the bus out to the east of Albuquerque and visit the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History. I had studied the Cold War at A-Level and so the pre-Hiroshima nuclear tests in New Mexico were covered, and then I revisited them in greater depth whilst studying the history of the American Southwest over the past couple of months. Sadly this meant the museum did not contain a huge amount of new material, although it was much more relevant revising the A-Level information now that I am actually in New Mexico! The museum had replicas of the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki respectively, and it also had an outdoor display area with B-29 and B-52 bombers and a few smaller planes and missiles. The narrative of the museum ran from the start of World War II right up to the present day and covered several aspects of nuclear technology that is probably not mainstream knowledge outside New Mexico, such as the exploitation of the Navajo people by employing them to mine the uranium found on their traditional lands and the fact that the USA's largest ever spill of radioactive material happened not at Three Mile Island, but at Church Rock in New Mexico in July 1979, although the fact that its effects were more environmental than human meant it is not as widely acknowledged as Three Mile Island. Such new information meant the museum was definitely worth the entrance fee as it improved my understanding of how nuclear development has affected New Mexico, even if it did not drastically increase my general overview of Cold War atomic science.

|

| Replicas of Little Boy (foreground) and Fat Man (background) |

|

'Gadget' - the first atomic bomb, which was exploded

at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in July 1945 |

|

An example of a 'Broken Arrow', a damaged

but undetonated nuclear weapon |

|

| B-52 bomber |

No comments:

Post a Comment